Unexpected connections to the past from volunteer Olivia

When I moved into my college accommodation this year, ready to start my final year at university, I was intrigued to find a plaque above the doorway, to one ‘H. Huggard’, with ‘Gallipoli 1915’ inscribed below it. I was immediately drawn to find out more – to develop this man’s story, and his connection to my room, into more than just a small plaque. This led further to an investigation into the university during the war, and the role that the city played in the ‘War to End All Wars’.

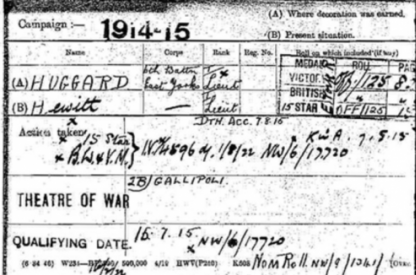

Lieutenant Hewitt Huggard, image from dungannonwardead.com

Hewitt Huggard was born on 5th August 1889, the eldest son of Reverend Richard Huggard, MBE, and Frances Marion Huggard (née Lloyd), in Tuam, county Galway. His family then moved to Dublin, before returning to Reverend Huggard’s town of birth, Dungannon, and then St John’s Vicarage, Barnsley. He attended Bronsgrove School between 1904 and 1908, before taking a second-class degree in History at Merton College in 1911, and enlisting in August of 1914. With the war starting on 28th July, this makes him one of the earliest to sign up; we can imagine that he would have felt eager to do his duty for his country. Hewitt then served in Egypt before being sent to Gallipoli. He was then reported wounded and missing during an attack on Tekke Tepe Ridge, at Suvla Bay, on 9th August 1915. He was later confirmed dead, at the age of just 26. He is commemorated on the Helles Memorial at Turkey (Panel 52-55), as well as the Dungannon war memorial in County Tyrone, the Roll of Honour in the East Yorkshire Regimental Chapel, Beverly Minster, Yorkshire, and on Merton College’s War Memorial. Unfortunately for the Huggard family, Hewitt’s brother Lewis was also killed in the war; they are not the only family to have lost multiple members in the conflict, as attested by the matching surnames on war memorials all over the country.

However, Hewitt was not acting in isolation; he was one of many students of the University who joined up (by 1918, virtually all fellows were in uniform and the student population in residence was reduced to just 12% of the pre-war total), and Oxford locals joined the forces in droves. As well as this, the city saw less obvious changes including the production of around 2000 mine sinkers a week by the Morris factory, and the 9th Duke of Marlborough speaking in the House of Lords about the loss of labourers to the forces, and the idea of bringing women in to replace them (as well as digging up the flowerbeds and lawns of Blenheim for vegetables and crops!). For those less actively engaged in the war, the effects were no less noted. The letters of Violet Bonfiglioli, an Oxford resident during the war years, reveal what life was like for her family in the city at the time: her son Owen, at just 17, was conscripted and sent to France; she was harassed in the street for handing out pacifist leaflets; noted soldiers drilling in the parks, and the city gull of hospitals and wounded soldiers. One of the things that many struggled with, understandably, was the lack of food: Mrs Bonfiglioli described getting to the shops before 8am and arriving to a queue of around 100 people! While it should not be surprising, in such an old building, to know that my predecessors would have been involved in such world-encompassing events as World War I, to come face-to-face with a name made the connection, and the history of the building, much more personal.

You can read more about Oxford’s war efforts during 20th century here.

Written by MOX volunteer Olivia Jenkins.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.

Sources:

https://cherwell.org/2014/07/28/oxford-in-world-war-i/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01x0km3