What role did the people of Oxford play during times of war?

For hundreds of years, war and conflict have been part of the fabric of Oxford’s stories: through Oxfordshire people’s experiences of it, and through the effect it has had on Oxford’s physical appearance. This was true too throughout the 1900s, when Oxford was irrevocably impacted by multiple wars: the First World War, Spanish Civil War, Second World War, and Cold War.

First World War

The ‘Great War’ created and highlighted extensive connections between Oxford and the wider world. Not only did many men and women from Oxford travel overseas to serve, Belgian refugees also arrived in Oxford, and people from all over the world were sent from the war’s Western Front to be treated in Oxfordshire.

The war brought tangible changes to Oxford’s infrastructure. 3rd Southern General Hospital was located in a variety of the city’s buildings, including the Town Hall and the university’s Examination Schools. Port Meadow was turned into an aerodrome for the Royal Flying Corps. Botley Cemetery saw the addition of more than a hundred Imperial War Graves Commission burials: soldiers who had died in hospital.

Hardit Singh Malik, the first Indian fighter pilot

The people of Oxford experienced the conflict in many different ways. Many had relatives who were serving overseas, and kept in touch with them through letters. Others were University of Oxford students, for whom the war elicited very strong beliefs; including Constance Coltman, who was a pacifist and became the first female Christian minister in the UK; Hardit Singh Malik, who fought racial prejudice to became the first Indian fighter pilot; and Rajani Palme Dutte, who was a conscientious objector. The war also prompted Oxford people to respond artistically. One of Oxford’s most famous examples is the poet May Wedderburn Cannan, who published two volumes of poetry about the war and its aftermath; she had volunteered at the front and also lost her fiancé, and later detailed her wartime experiences and grief in her autobiography. For her, and many others, life in Oxford could not just resume after the war; people had to adjust to new realities.

Spanish Civil War

Between 1936-39, approximately 35,000 people from 50 countries went to Spain to join the International Brigades, a combatant organisation supporting the Spanish Republicans against a fascist attempt by a group called the Nationalists to overthrow the government. 31 volunteers from Oxfordshire were among those supporting the Brigades, and six of them died: Anthony Carritt, Edward Cooper, Lewis Clive, Herbert Fisher, Ralph Fox, and John Rickman. In June 2017, a memorial to these volunteers was unveiled in Oxford in St Clement’s, outside South Park: it depicts a fist crushing a scorpion, representing democracy quashing the ‘poison’ of fascism. The war ended in 1939 when the Nationalists won, and their leader General Franco ruled Spain until his death in 1975.

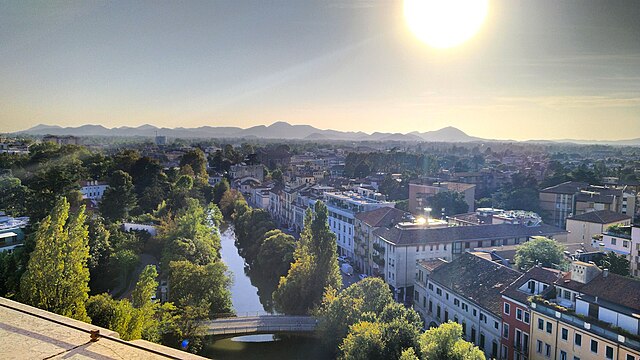

Second World War

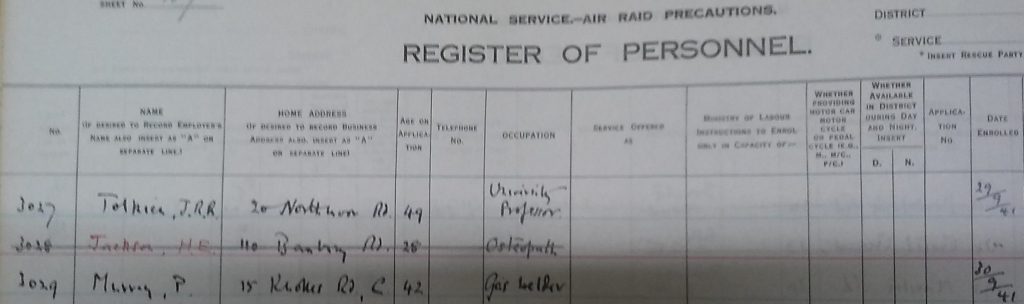

Oxford was particularly affected by the aerial aspect of the Second World War. The county became home to numerous training airfields for glider pilots and bomber crews, and also provided repairs for fighter planes. In 1939 the Air Ministry had designated Cowley as one of six depots for aircraft repair in the country. The airfields became bombing targets for German planes, causing military and civilian deaths as well as significant structural damage. The people of Oxford also endured the hardships of wartime experienced throughout the country: blackouts, rationing, and preparations for the invasion, including forming a Home Guard. Oxford’s Home Guard was ‘the 6th Oxfordshire Battalion,’ and one of their most significant roles was to guard factories, railway stations, and gas works at night.

J.R.R. Tolkien was an Aid Raid Precaution warden during the Second World War

As the people of Oxford said goodbye to their loved ones – men and women – who had left to serve, they also welcomed newcomers: evacuees, mainly children. Oxford’s allotted evacuees largely arrived grouped according to school, and by 6 September 1939 the county had welcome 19,830 official refugees. Villages throughout Oxfordshire, including Hailey and Finstock accepted two waves of evacuees in 1939 and 1940. The fabric of our community has always been changing, not static; these Second World War examples are amongst many over Oxford’s hundreds of years of history, including up to the present day.

Cold War

The decades after the Second World War saw another kind of conflict; the Cold War. This did not result in Oxfordshire deaths or involvement in outright conflict, but saw significant anticipatory preparations occur. Archival documents reveal the detailed plans that were drawn up calculating predicted death rates should there be a nuclear attack on Oxford. Air raid shelters were also constructed throughout the city, based on population estimates of how many people would need to be safely housed by them if an attack were to occur during peak shopping and travelling hours.

The threat of nuclear war also necessitated plans for how to manage emergency operations. From 1954, the Civil Defense organised new training and equipment in hopes of best responding to the unique challenges that a nuclear attack would present. The Corps was divided into Headquarters Sections, each of which were equipped with mobile control centres and means for repairing communication lines and measuring radiation in the area.

Cold War fears necessitated new additions to the Oxford landscape, above and below ground. Underground bunkers were commissioned to serve as headquarters for observer corps; one such bunker was built in 1965 on James Wolfe Road in Cowley, and was still in use until 1992. Above ground, the former First World War air force base at Upper Heyford became a significant tactical and command centre for the US Air Force in the 1960s-70s, housing bomber and reconnaissance aircraft. The base was not closed until the 1990s; it has since been the subject of a failed attempt to award it status as a protected heritage site.

Written by Dr Hanna Smyth, research consultant and former volunteer, as part of a Heritage Seed Fund project.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.