Royalists, Recipes and Real Hardship

Ann, Lady Fanshawe, by Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen (c) Valence House Museum; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

Ann Fanshawe (1625 – 1680) is known chiefly for her writing, including a memoir detailing her time in the Royalist court at Oxford during the English Civil War, her exile with her husband during the Interregnum and her life as a diplomat’s wife in Europe following the Restoration. She is also known for her recipes influenced by her time spent in Spain and Portugal, among them the first recorded recipe for ice cream. She is remembered as a stoical and dutiful wife, performing the role she had been trained for despite the interruption of a war that divided the country, and finding purpose amid war, political upheaval, exile and personal loss.

Civil War

Charles I in Three Positions by van Dyck, 1635–36

The English Civil War was fought from 1642 to 1651 between the Parliamentarians and the Royalists, over the right to rule the three kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. Choosing a side was a complex choice, with class, financial, geographical and religious considerations. The Royalists, also known as Cavaliers, supported King Charles I and his divine right to rule, and were often stereotyped as flamboyant and wealthy, with Catholic sympathies. The Parliamentarians tended to be more puritanical, and fought for the abolition of the monarchy.

The country was divided up into Royalist and Parliamentarian held regions. Parliament seized London and forced many prominent Royalists out. They were based mostly in the South and South-East, controlling most major ports, including London, Hull, and Portsmouth, the largest arsenals and the Navy. The King held the North, the port of Newcastle, most of Wales and Cornwall. Those that found themselves occupied by their enemy fled if they were able, abandoning their homes and belongings.

Royalist Oxford

Oxford became the centre of Royalist power, and the location of the royal court after it was exiled from Parliamentarian held London. Royalist sympathisers followed the King initially from London to York, but eventually found refuge in Oxford. Wealthy families with ties to the King followed him to enjoy the protection of his army and to have their voices heard at court. Some gave all their money to the Royalist cause. Their homes ransacked by Parliamentarian forces and their pockets now empty, all they could do was hope that the King would remember their sacrifice. They stayed close to him, so that if he were to triumph, they would be in a position to benefit.

Portrait of Prince Rupert, Colonel William Legge (probably) and Colonel John Russell, three Royalist Commanders based in Oxford. Artist William Dobson. Image copyright Ashmolean Museum.

The situation in Oxford was not to everyone’s liking. Landowners, lords and established men had fled their estates and were now living in cramped conditions well below the station they were accustomed to. Oxford, once a city of students, became home to soldiers and refugees. Colleges were repurposed as armouries, livestock roamed the university gardens and the run-off from slaughterhouses ran through the street, bringing disease with it. The drainage system collapsed under the sudden influx of fifteen thousand people, and plague broke out in 1644, with no way to improve the unsanitary conditions.

Exceptional Women

Still, the disruption of life on the run made for interesting circumstances for the young women caught up in it. There are numerous tales of women doing exceptional things during the Civil War, both Royalist and Parliamentarian. For example, the puritan Lady Brilliana Harley defended her home, Bramptom Bryan Castle, during a three month siege by Royalist troops in 1643.

Similarly, Lady Mary Bankes, a Royalist, kept Parliamentarian forces at bay for three years outside Corfe Castle in Dorset with only a handful of men and her household staff. It was a time of social flux and traditional gender roles slipped in importance when men were either away fighting, imprisoned or dead, and property needed to be defended.

People, women especially, adapted and did whatever they could to survive, regardless of the social protocol of years prior. Particularly visible are the stories of the social class of women raised to become the ladies of fine estates, who were suddenly thrust into a highly politicised and militaristic world, with genuine threat from which they would have to defend themselves. Choices and actions that were unthinkable had suddenly become the everyday fabric of their lives. Many young women found themselves in a strange position. The world they had been waiting for had failed to materialise. Instead a stranger and more dangerous one stood in its place, one they had not been prepared to navigate. Even where they were technically safe from the worst of the war, there was a certain informality and suspension of normal protocol. Satirical pamphlets of the time noted women’s increased involvement in politics, which was now inescapable for most people, and portrayed it as a kind of moral failing, or a criticism of the traditional patriarchal society.

Ann Fanshawe

Ann Fanshawe was a teenager when war broke out. She was born in London, and lived in a Hertfordshire estate with her father and sister. Ann was accomplished and wealthy, but also adventurous, energetic and tomboyish. Her father, John Harrison was born in Lancaster, the twelfth son of a yeoman, and moved to London when he was twenty-two years old, with nothing but his education. He rose up through the treasury, becoming the Commissioner for Customs, an MP and the first Commissioner of Customs. He built his Hertfordshire estate and was knighted in 1641. John owed everything he had to the King, and so was a fiercely loyal Royalist.

When war broke out, everything John Harrison had built came tumbling down. Parliamentarian forces attempted to apprehend him in London, and he managed to evade his captors, claiming he had to retrieve some papers that would surely be needed. He sent word to Ann and her sister to flee to Oxford. Ann took almost nothing with her, but made sure to remember the collection of her late mother’s writings, including family recipes and remedies. These papers were crucially important to Ann, a way to remember her mother and to remember the life they had together. Perhaps this memory, of fleeing her home with the papers, would inspire Ann later in life to leave her own children a collection of her writing in the form of a memoir.

Ann’s memoir tells us a great deal about her time at the Royalist court in Oxford. Her family experienced a total reversal fortunes. Her father had given everything they had to the King, and their estate in Hertfordshire was ransacked by Parliamentarian forces. It was impossible for them to return either to their home or to their comfortable circumstances. According to Ann, the family lived in one room, subsisting on one meal a day, with few clothes and possessions. The talk in Oxford was only of war or the sickness that was rampant due to the overcrowding.

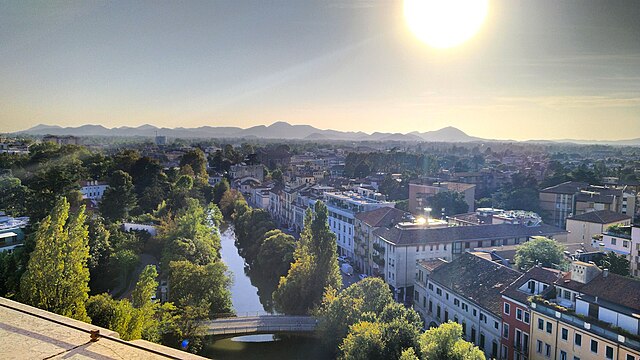

Wyck, Jan; The Siege of Oxford; Oxfordshire County Museums Service;

However, Ann notes that most people bore the suffering well enough, and found ways to be cheerful despite their circumstances. Many families, like hers, had been wealthy and were now experiencing real hardship. They were alive though, and there was comfort to be had in shared circumstances. Oxford quickly became unrecognisable, transforming into a garrison town. There were families living in the student accommodation, and taking up spare rooms in civilian homes. In St Aldates there were five strangers each in the seventy-five houses recorded, including various tradespeople who catered to the King and his court. These court servants were unpaid, so the court devised its own currency to pay the people of Oxford for goods or as wages. The residents of Oxford, who had been there before it became the King’s stronghold, whether they sympathised with the Royalists or Parliamentarians or neither, could not escape the situation. The population exploded as Oxford took in more and more refugees, as the siege lines moved across the country. Ann remarks in her memoir on the “sad spectacle of war” that defined the lives of the displaced families in Oxford, but it was also exciting to her. There was a sense of adventure and the kind of high-stakes political tension that she would never have known living in a country estate far from court. She found purpose amid the chaos, and it was here that she met her future husband.

Sir Richard Fanshawe

Ann met Sir Richard Fanshawe staying in Oxford. He had been away in Europe, working as a diplomat for most of the 1630s, but had returned to Oxford in 1643 to serve as a secretary to the Council of War, and to advise the future King, the Prince of Wales. Richard was seventeen years older than Ann, who was nineteen, and he was her second cousin. Anne was immediately besotted with him. Her memoir was written much later, after Richard’s death, so that could be a factor in her generous depiction of him and of their relationship. Still, she claims that her life only truly began after they had been married.

Their wedding was held at Wolvercote Church, just outside Oxford. Ann, like many other young women during this time, had no dowry to give, nor any money of her own. She could only promise him her devotion, and he the same. Their relationship would be a stable foundation all their lives, through the chaos of war, overseas adventures, the comings and goings of kings, miscarriages and misfortune.

Richard followed the troops, providing counsel, and Ann went with him, raising funds for the Royalist forces. The country was racked by famine, rife with bandits and raiders, and falling to the Parliamentarians. The war ended in September 1651 with a decisive Parliamentarian victory at the Battle of Worcester. King Charles was captured, imprisoned and ultimately executed. His heir, the Prince of Wales, was exiled and the monarchy was replaced with the Commonwealth of England, led by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell. Ann Fanshawe and her husband fled England by ship, alongside other Royalists keen to escape the oncoming Parliamentarian forces. They travelled around Europe as political refugees, aided by Richard’s diplomatic ties and ability with foreign languages.

In 1660, Charles II returned to England and to the throne, following the death of Oliver Cromwell and some years of unstable government. The exiled Royalists were finally free to return. Richard Fanshawe was made the ambassador to Portugal, and organised the marriage of King Charles II to the Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza. Richard, and Ann along with him, was then sent to Spain to serve as the ambassador to Spanish King until his death in 1666. Anne then finally returned to England with her children. She and Richard had sixteen children, of which five survived, four daughters and one son. She spent her final years working on her memoir. She also made a collection of the recipes she had learned throughout her life. These included folk remedies for common ailments. It was common for women to have knowledge of such medicinal preparations, which were often passed down through the generations. Perhaps Ann’s remedies were taken from her mother’s writings, among the papers that Ann had taken from her Hertfordshire estate and brought to Oxford. Ann also documented the recipes she had learned while travelling in Spain and Portugal with her husband, including ones for ice cream and sangria.

House of the Seven Chimneys, Madrid, where Ann and Richard Fanshawe lived in Spain (c) Louis Garcia https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0

Ann Fanshawe has left us a wealth of written evidence about the effects of the societal upheaval of the Civil War on women in her social class. The particular problems that faced young women emerging into a world completely changed by war and the breakdown of social norms are recorded in Ann’s recollections of her own life. Through these uncertainties, new possibilities emerged, which afforded women like Ann the rare opportunity to forge a new path and to live exceptional and unexpected lives.

Written and researched by MOX volunteer Elizabeth Kuligowski.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.