This blog post was written and researched by MOX volunteer Iulia Costache.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.

Pre-newspaper times

Even though the printing press was introduced to England in 1476, it was only in the 16th century that printed news took off, and even then, at a very slow pace, due to the necessity of town criers to provide them, stemming from the illiteracy of the general population. Early forms of printed news varied from printed news books to news pamphlets and usually related information pertaining to a singular event (e.g., battles, disasters or public celebrations). The earliest record of such a pamphlet details an eyewitness account of the Battle of Flodden (1513) between the English and the Scots, where the former were victorious. However, the Tudors kept strict control over the dissemination of news, preferring its delivery from church pulpits. Furthermore, by the 1500s, all printing matters were reserved to royal jurisdiction. King Henry VIII (r.1509-1547) issued a list of proscribed books in 1529. Nine years later he proclaimed that books needed to be examined and licensed by the Privy Council, or its deputies, to be published and did not allow for any unlicensed books to be published. Mary I (r.1553-1558) provided the Stationers’ Company, a guild of stationers tasked with handling the trade of books and related activities, with a charter in 1557. As a result of this charter, the Company now held the right to find and seize unlawful or pirated works. The Stationers’ Company was given further measures of control and licensing during the reign of Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603) due, in part, to concerns over the circulations of material which attacked or undermined the queen’s religious settlement of 1559.

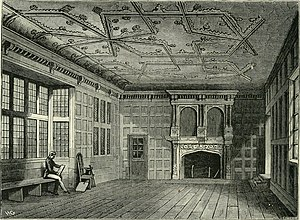

Engraving of the Star Chamber, published in “Old and new London” in 1873, taken from a drawing made in 1836

The Star Chamber, a court consisting of judges and privy councillors, supplementary to common-law courts, thus put forth a decree in 1586, in which print trade became heavily regulated and the publication of news was wholly forbidden. This decree restricted printing to only London, with the exception of two other printing presses, one at the University of Cambridge and one at the University of Oxford. A petition for the recognition of a press was put forth to Elizabeth I, two years earlier, by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and Chancellor of the University of Oxford. The decree granted the University one printer and printing press.

The need for news

Considering the strict control over printed content in England, the first newspapers to be printed in English were called corantos, published in Amsterdam around 1620 and smuggled into England. A group of London publishers and printers began circulating printed sheets with news in this style shortly after, and one of them, Thomas Archer, was even jailed for printing corantos without permission. In 1621, a translated version of a Dutch coranto called Corante, or, newes from Italy, Germany, Hungarie, Spaine and France was published. The content of this work contained no information on national news, but rather happenings around Europe, with a focus on the Thirty Years War. The Thirty Years War became a widespread media phenomenon and it ultimately led to the suspension of news publications between 1632 and 1638, by order of the Star Chamber, due to complaints of unfair coverage from Spanish and Austrian diplomats.

England at this time was ruled by Charles I (r. 1625-49), who believed in the divine right of kings, meaning that no one but God could overrule him. For 11 years he led England under Personal Rule, having dissolved Parliament and ruled by decree. In February 1640 he had no choice but to summon Parliament (also known as Short Parliament), as he needed funds to finance the Bishops’ Wars in Scotland. However, he dissolved it after only three weeks, as Parliament was more concerned about addressing numerous grievances they had with him. After losing the poorly funded Bishops’ War, Charles I had no choice but to recall Parliament for a second time (Long Parliament). In 1641, the Star Chamber was abolished by the Parliament, with the passing of the Habeas Corpus Act of 1640. Without copyright laws being enforced, media was freer than ever without restrictions, and there was a high demand for news to keep up with the events of the Civil War. Both pro-Royalist and pro-Parliamentarian publications were printed to drum up support from the public on each side.

Portrait by John Michael Wright, depicting Charles II in Garter robes

The amount of printed material expanded tenfold during 1640 and 1660, before the Restoration began with the return of the monarchy, Charles II being throned more than a decade after his father, Charles I, was executed at Whitehall. Upon his return he was dismayed at the state of printed material in his kingdom. All sorts of scandalous books and media could be found on the streets of London and he decided that he needed to instate an act that would prevent ‘the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Bookes and Pamphlets and for regulating of Printing and Printing Presses’. The Licensing of the Press Act 1662 declared that all publications needed to be approved by the Government-controlled Stationers’ Company, that representatives of the king could search for and confiscate any ‘unlawful’ material, and that offenders would be fined or imprisoned. The number of printing places in London were reduced to 20, and outside of that, only Oxford and Cambridge were allowed to print.

The Oxford Gazette

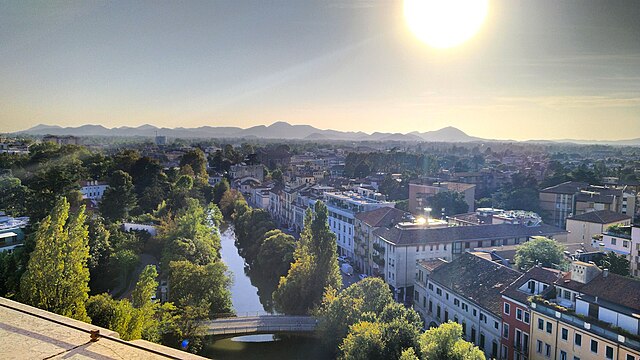

In 1663, Sir Roger L’Estrange, journalist and pamphleteer, was appointed surveyor of the imprimery as a reward for his loyalty to the royalist cause. The role granted him the power over materials that were allowed to be printed, and he relentlessly eliminated any anti-government propaganda from unlicensed printers. In this role he also gained control over the official governmental newsbook, ‘The Intelligencer’, considered by some to be the first English newspaper. This publication ran for three years prior to his appointment to this role, by his predecessors Henry Muddiman and Sir John Birkenhead. However, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War, the need for comprehensive, precise information became very sought-after, and the Court was not impressed with L’Estrange’s coverage. In the early spring of 1665, the Great Plague took over London, the death toll increasing over the summer months rapidly. In July, Charles II moved his court first to Hampton, then to Oxford, where it remained until late January to try and escape the disease. Courtesans were even wary of handling newspapers from the capital, afraid of potential contagion. Charles II, rather than going without news, ordered for an official periodical to be published using the University Press.

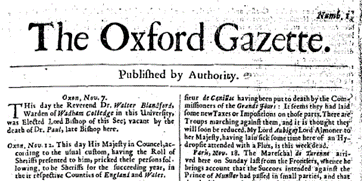

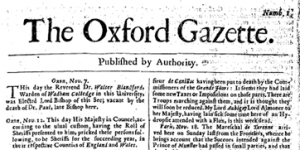

Snippet of the first edition of the Oxford Gazette, dated 7 November, ‘Published by Authority’

On the 7th of November, 1665, Henry Muddiman returned to his role to publish a newspaper called ‘The Oxford Gazette’ twice a week. It was later known as ‘The London Gazette’, its name changing as the court returned to London. This publication was not widely circulated, being made available only to subscribers and sent via post. The London Gazette, having run over 350 years and counting, is widely believed to be the oldest continuously published newspaper in the United Kingdom.

References

https://newsmediauk.org/history-of-british-newspapers/

https://www.britannica.com/topic/newspaper

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/inspire-me/18th-century-satire-and-scandal/

http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/european-media/censorship-and-freedom-of-the-press

https://academic-accelerator.com/encyclopedia/history-of-british-newspapers

https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=commentary_uk_1586

https://blogs.bl.uk/thenewsroom/2021/09/400-years-of-british-newspapers.html

https://www.britannica.com/topic/publishing/The-flourishing-book-trade-1550-1800

https://oupacademic.tumblr.com/post/53710102363/1586-decree-of-star-chamber-grants-the-university

https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/the-english-civil-war-and-the-rise-of-journalism/

https://www.britannica.com/event/English-Civil-Wars#ref932079

https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/restoration

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232564976.pdf

https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/17219056/677787.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1660-1690/member/l8217estrange-roger-1616-1704

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Roger-LEstrange

https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/8370/Taylor_ku_0099D_11423_DATA_1.pdf;sequence=1