Campaigning for compassion in Victorian Oxford

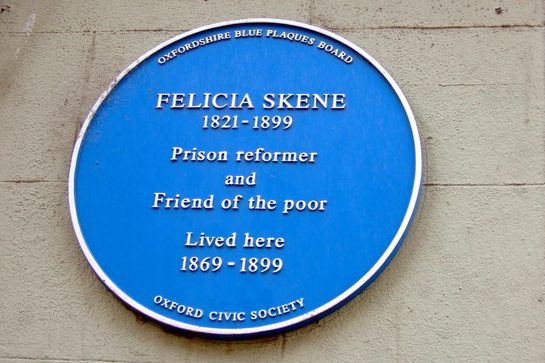

Felicia Skene was a writer, reformer and philanthropist working in Oxford during the Victorian period. She is best known for her work within the Oxford Prison system as a dedicated supporter of prison inmates and campaigner for prison reform. Skene also worked with Oxford’s sex workers and homeless population and set up refuge for women fleeing sex work and domestic violence. She wrote many books and articles and used the money she made to fund her philanthropic work. Her home in St Michael’s Street was known as ‘The Skene Arms’ because it was always open to sex workers and the homeless as well as clergymen, politicians and students. A blue plaque marks her residence at 34 St Michael’s Street in Oxford, in honour of the great work she did throughout her life as a prison reformer and friend of the poor.

Felicia Skene devoted much of her time to what we now know as social work, though social work didn’t exist in Victorian times in a formal sense and in the way it does now; those in need relied predominantly on the voluntary work of women, organising and performing all sorts of charitable works for the benefit of the community. In 1854, there was a terrible outbreak of cholera and smallpox across Oxford. Skene was tireless in her efforts to help and care for those Oxford communities that were suffering and to recruiting and training other woman to join her in her arduous task. Skene visited, comforted and cared for those who were sick, as well as training, organising and supporting nurses to help care for them. Some of the nurses trained by Skene, went on to work in the Crimea with Florence Nightingale.

Skene went on to work with the homeless population of Oxford, and to support the many sex workers in the city. It was whilst working with the sex workers of Oxford that Felicia found her next calling – her prison reform work. Sex workers would often end up in jail and so through helping these young women, Skene discovered a lot of work to be done in the prison service and in reforming it. She began visiting the prisons, mostly women’s prisons, and would offer support and advice. In 1878 Skene was appointed official ‘Prison Visitor’ at the Oxford Castle and Prison, making her the first woman in England to be appointed to the role. Skene would meet women released from prison at the gates at 6am and take them to her home, where she would give them breakfast and offer practical assistance, often finding them a job, in order to keep them off the streets.

Skene believed that prisons should be places of rehabilitation rather than merely places of punishment. She believed that the inmates could be reformed by forming relationships with people who visited the prison and provided counsel. Skene stated in her writing “experience had shown that even the most lawless spirits can be tamed by kindness when once their affections have been roused.” Whilst Skene accepted that some small proportion of prisoners may not be reformable, she argued that even for those “professional thieves and villains”, the most difficult to reach, “the memory of wise and true words… [might] bear fruit in a tardy repentance”.

Skene was hopeful, not only of the powers of human connection and the ability of such connection and support to do tremendous good and to reform the lives of those who had found themselves in prison. But also, hopeful that future generations would come to see things in the way she did, that they would prioritise rehabilitation over punishment and see the possibilities that working with prisoners might have. Skene believed that the “best and noblest” of her generation’s children were “fired with the enthusiasm of humanity”.

Skene made a huge contribution to the prison reform movement of the 19th century, campaigning for rehabilitation in prisons, for the abolition of the death penalty and for the decriminalisation of suicide. Skene wrote articles detailing her experiences in prisons as well as a novel called Hidden Depths which is based on her experiences and contains many scenes which describe real events. Skene was a successful author and used the money she made from her writing to fund her philanthropy. Unfortunately, Skene died in 1899 and would not see the prison reforms of the following century put into practice. None-the-less, the work of Skene and others in popularising the idea of prisons as rehabilitating institutions took hold and in the first two thirds of the 20th century, British governments would introduce new penal policies which emphasised reform over punishment. Young offenders were treated separately from adult offenders, efforts were made to keep people out of custody through the use of probation and prison life focused more on rehabilitation. In 1961 suicide was decriminalised and in 1965 capital punishment was abolished. Skene helped many people over the course of her life, both in a very practical way and by using her writing to influence wider policy. She is remembered here in Oxford as an incredible woman who worked tirelessly to help those in need and to reform those services which could do more to support them.

Written by volunteer Laura Lys – creator of the Riot Room, a space dedicated to the promotion of women and women-centred culture.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.