The only known Black British man to have fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War

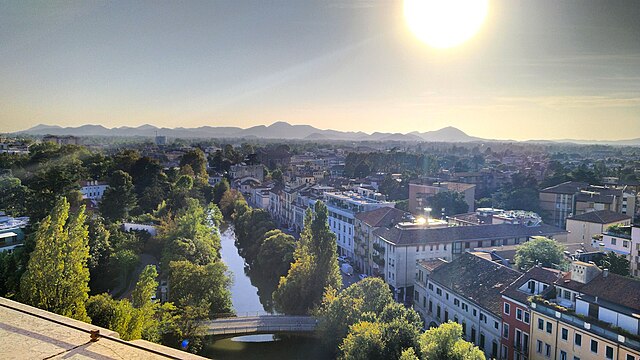

Photograph of a mural dedicated to Charlie Hutchison, painted on the wall of Coffee#1 which opened in 2021, Witney, Oxfordshire. Image taken in April 2022.

“I am half Black, I grew up in the National Children’s Home and Orphanage. Fascism meant hunger and war”.

Of the countless people born in Oxfordshire, few lived such an incredible life as Charlie Hutchison. Born in 1918, Charlie became the only known Black British man to have fought against fascism in the Spanish Civil War. He was also among the first to travel to Spain, one of the youngest, and also one of the longest serving volunteers. His life-long hatred of fascism would bring him to participate in many key events in history, including the Battle of Cable Street, the Dunkirk Evacuation, the liberation of France and Italy. During WWII he also took part in the liberation of Belsen concentration camp. Charlie spent 10 years fighting a bloody crusade against various fascist movements throughout Europe. Upon returning to Britain he married the love of his life and started a family, adopting foster children, continuing his trade union activism, and playing a role in the commemoration of British anti-fascists who fought in Spain.

Despite all his achievements, his life story had gone entirely unnoticed by Oxford historians until very recently. When the Oxford Spanish Civil War Memorial was unveiled in 2017, Charlie Hutchison was not recognised among the 31 known people with links to Oxfordshire to whom the memorial had been dedicated to. Despite being overlooked by professional historians, his achievements were eventually made public knowledge in 2019 thanks to a project by London school children.

Note: This article contains never-before published photographs of Charlie Hutchison, provided by Charlie Hutchison’s daughter Susan Lilian Small and published on the Museum of Oxford website with her permission.

Photograph of Charlie Hutchison (right) taken during WWII. Image provided by Susan Lilian Small.

Charlie’s early life (1918-1935)

Charlie Hutchison was born on the 10 May 1918, in a tiny historic village called Eynsham on the outskirts of Oxford. Some writers have mistakenly named Witney as Charlie’s birthplace, however Charlie Hutchison, his family, and birth certificate, have all been found to credit Eynsham as Charlie’s birthplace. His true birthplace was discovered after a shop in Witney had already created a mural dedicated to Charlie Hutchison. His mother, Lily Rose, was a white British woman and his father, Charles Francis, was a Black man from the Gold Coast (Ghana) who went on to author the famous book The Pen Pictures of Modern Africans and African Celebrities. During his childhood, the family fell into extreme poverty after Charlie’s father returned to the Gold Coast in 1923. With the family unable to afford to look after all the children, Charlie and one of his sisters were sent to live in a National Children’s Home and Orphanage in Harpenden, Hertfordshire between 1930-1933. When Charlie’s father learned that his children had been placed in an orphanage he wanted to take them into his care. However, so much time had passed that since he last lived in England that he had become a stranger to the family and the children were not familiar with him.

After leaving the orphanage Charlie moved to Fulham in London and became a lorry driver. He also joined the Transport & General Workers Union (now called Unite), which he would support for the rest of his life. By 1935 Charlie had joined the Fulham branch of the Communist Party of Britain and their youth wing the Young Communist League. He was so impressed with the communist’s commitment to fighting against fascism that he became a lifelong communist activist and went onto become the chairman of his local branch of the Young Communist League. These experiences were by no means unique, as many of Britain’s leading 20th century Black civil rights activists would also join the communist movement, all of whom cited poverty and racism as their motivation to become Marxists. Some notable figures include Claudia Jones, Trevor Carter, Dorothy Kuya, Henry Gunter, Billy Strachan, Len Johnson, and Peter Blackman, to name only a few examples. Charlie’s involvement in the communist movement led him to become involved in the Battle of Cable Street in 1936, a street battle between the British Union of Fascists and their opponents which saw the fascists abandon their march and retreat. In the words of one historian, Charlie “felt with the Jewish volunteers that fascism was a very real threat to his existence, beyond any theoretical abstraction.”

A photograph taken in 1937 of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion in Spain, whose leader was the first African-American in history to command white troops in battle. Unknown photographer.

Arrival in Spain (1936)

Come 1936 Spain’s nationalist led military would rebel against the Spanish republican government. The nationalists would embrace fascism and receive military support from both Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, while the republic would receive support from the Soviet Union and leftist movements across the globe. The Communist Party of Great Britain would work closely with the Soviet Union to recruit volunteers from Britain to fight against fascism in Spain, managing to recruit approximately 2,500 people.

Charlie Hutchison was one of these 2,500 volunteers and is recognised by historians as being the only known Black British man to have fought against fascism in Spain. Not only was he the only Black British volunteer but he was also one of the youngest volunteers, and one of the longest serving. Other English speaking Black men would join from America, including the famous communist Oliver Law who became the first Black American to lead white troops into battle. Charlie was not the only man with strong links to Oxfordshire who fought against fascism in Spain, as historians have identified at least 31 others, the most famous of which would be George Orwell. Although Charlie had been living in London before travelling to Spain, he identified as coming from Oxford and named the city as his place of origin on Spanish documents.

Charlie left for Spain in late 1936 and was noted by the Special Branch (police spies) to have left for Spain to become a machine gunner. The British Battalion which hosted volunteers from the UK had not yet been formed so Charlie joined British and Irish volunteers in the No.1 company of the French dominated Marseillaise Battalion of the 14th International Brigade. Charlie and other volunteers from Britain and Ireland were then sent to Lopera where they were outnumbered and outgunned by fascist forces. The volunteers were badly beaten by the fascists who used their air superiority to cause massive casualties against the volunteers, the most famous victim of which happened to be Darwin’s grandson John Cornford. Charlie was badly wounded during the fighting, however he was lucky to survive a battle in which so many of his fellow volunteers had perished.

Time as an ambulance driver (1937-1938)

Due to his young age and possibly spurred by his wounds, Charlie Hutchison was informed by his superiors that he was to be sent back home to Britain. However, Charlie protested against this decision and insisted that he be allowed to stay in Spain. According to Bill Alexander, the future leader of the British anti-fascists in Spain, Charlie refused to leave. As a compromise Charlie was kept in Spain but was instead moved from being a soldier to becoming an ambulance driver for the 5th Republican Army Corps. During his time as an ambulance driver he served with distinction and was noted by his commanding officer, Harry Evans, for being a ‘hard and capable worker’. Although Charlie had argued to stay in Spain, his attitude would soon change. After a letter was sent by Charlie’s mother in April 1937 requesting that Charlie be sent home, he no longer wished to stay in Spain and began asking his commanders to be allowed to return. This decision to leave Spain is believed to have been influenced by news of the ailing health of Charlie’s stepfather who had been sent sent to a hospital after suffering a serious gastric related illness. For the next few months Charlie tried multiple times to convince his commanders to send him back home, but his requests were bounced around to different commanders and never acted on. It appears as though in the chaos of the war, Charlie’s requests had been lost and forgotten. On 6th December 1939 when his fellow British volunteers had been demobilised and crossed into France, Charlie was only released from service two weeks afterwards on 9th December.

The Second World War (1939-1945)

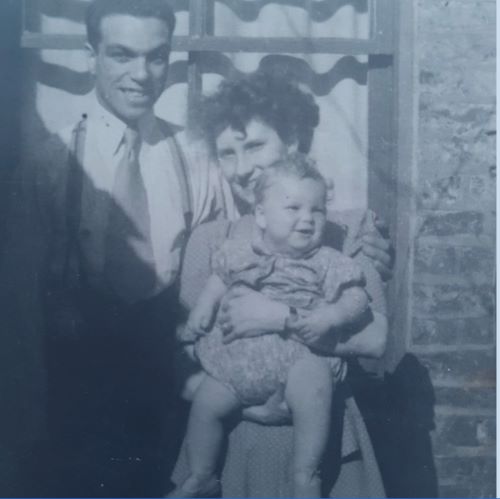

Charlie Hutchison and his wife posing with one of their children. Image provided by Susan Lilian Small.

After returning to the UK, Charlie continued to work as an organiser for the Fulham branch of the Young Communist League, although he found that he could not secure work. He dedicated himself to Spanish solidarity work, only for the Spanish republic to collapse in April 1939. However as fascists spread further across Europe, Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. Now given a chance to fight against fascism yet again, Charlie signed up to join the British military and was sent to France. The next year the war had gone south for Britain and Charlie found himself taking part in the 1940 Dunkirk Evacuation.

During WWII Charlie Hutchison was sent to many theatres across the war, he fought in North Africa, France, Germany, Italy, and by 1944 was serving with the British military in Iran. Then in April 1945 came one of the most horrific days in Charlie Hutchison’s life, the liberation of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. To cite one journalist, what Charlie saw at Belsen was “the end conclusion of the ideology he had dedicated his entire adult life to fighting.”

Charlie’s later life (1946-1993)

By the time Charlie Hutchison had left the British military in 1946, he had spent almost 10 years continuously fighting fascist movements across the world. When he returned to the UK he moved back to London and married a fellow communist Patricia Holloway in 1947. The couple had many children and lived the rest of their lives happily married in the south of England. Charlie worked various jobs his later life, spending his remaining years as a communist activist, trade union activist, and even played a role as a committee member for the successful campaign to raise a memorial to the International Brigade in London’s Jubilee Gardens. He died in Bournemouth Hospital in March 1993, leaving behind a family which continues to be deeply proud of his accomplishments.

Legacy – War Memorial (2017)

Photograph of Charlie Hutchison with his daughter Susan Lilian Small at her wedding. Image provided by Susan Lilian Small.

In 2015 a book was published titled No Other Way: Oxfordshire and the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. This special work attempted to track down all the known volunteers with links to Oxfordshire who travelled to Spain to fight fascism. No Other Way identified 31 of these volunteers, and the money from the book sales contributed to erecting the Oxford Spanish Civil War Memorial dedicated to the 31 volunteers near South Park.

Some notable examples include:

• Thora Silverthorne (1910-1999): Trained as a nurse in Oxford’s Radcliffe Camera, later co-founded the first union for working class nurses in Britain, treated hunger marchers moving through Oxford, and headed the first foreign hospital established in Spain during the Spanish Civil War

• Ralph Winston Fox (1900-1936): A linguist from Magdalen College who wrote the biographies of both Vladimir Lenin and Genghis Khan

• Lewis Clive (1910-1938): An Olympic gold medallist in rowing who studied at Christ Church

• Anthony Carritt (1914-1937): Brother of the communist spy Michael Carritt, and son of famous biologist Arthur Darbishire

• George Orwell (1903-1950): Author, journalist, and British government informer

• John Rickman (1910-1937): Expert on church architecture from Lincoln College

• Giles Romilly (1916-1967): Winston Churchill’s nephew

• Herbert Fisher (1910-1938): Relative of Virginia Woolf

• Edward Cooper (1912-1938): Actor and newspaper worker

In 2017 the long due memorial was erected in the city of Oxford to commemorate the 31 identified volunteers, and was built after a long battle with the local council and difficulties securing funding. The location on the outskirts of the city was due to the decision by city councillors to reject all planned locations for an anti-fascist memorial in the city centre.

In 2015 a book containing biographies of all 31 volunteers was published to raise money for the memorial, however Charlie Hutchison’s name was completely absent. The three separate historians who collaborated to write the book, alongside the Oxford professor who helped to review the work, appear to have been entirely unaware that Charlie Hutchison existed.

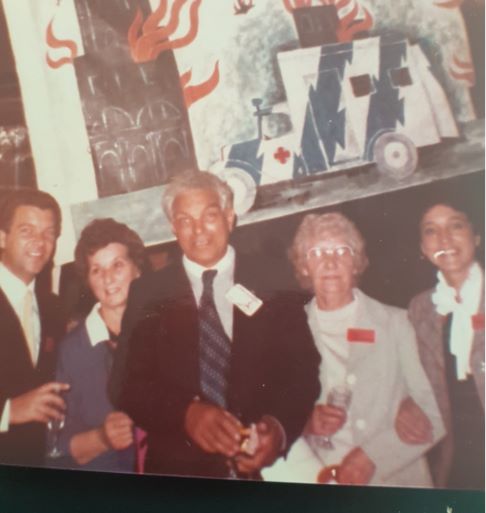

Charlie Hutchison (centre) in later life. Image provided by Susan Lilian Small.

Re-discovery (2019-present)

Charlie Hutchison was a very humble man and was not prone to bragging about his accomplishments. However this admirable personality trait had the unintended effect of making his life much harder for historians to accurately trace. Although traces of his existence were known to specialist historians (most notably Richard Baxell), the details of his life would not be known to the public until as late as 2019. In 2019 a memorial event dedicated to Charlie Hutchison was held at the Marx Memorial Library in London, showcasing a new research project headed by schoolchildren from London’s Newham Sixth Form College, and featuring Charlie Hutchison’s surviving family members. Details of Charlie’s time in Spain were primarily uncovered through documents unearthed by historian Richard Baxell, before a mini biography of Charlie’s life was published in the book Red Lives. This new event saw countless new details of Charlie’s life come to light for the first time, and is hailed as the moment when the exact details of Charlie’s life were first made public. It also led to the creation in 2021 of a project between students from the same College, the Marx Memorial Library, and Oxford’s Wadham College known as the Charlie Hutchison Project.

Written and researched by MOX volunteer Daniel Poole.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.

Want to read more about the communist movement in Oxford? Find out about strike leader Bill Firestone a.k.a. Abe Lazarus.

Bibliography for this piece:

Barnett, Marcus. “Britain’s Black International Brigadier.” Tribune Magazine, October 31, 2020. https://tribunemag.co.uk/2020/10/britains-black-international-brigadier (accessed April 13, 2022).

Baxell, Richard. “Charlie Hutchison.” NO PASARÁN 52 (2019): 8. http://www.international-brigades.org.uk/sites/default/files/NoPasaran3-2019Web.pdf (accessed April 13, 2022).

Baxell, Richard. “The British Battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939.” PhD diss. London School of Economics and Political Science, 21 December 2001. http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/1661/ (accessed April 13, 2022).

Farman, Chris. Valery Rose, Liz Woolley. No Other Way: Oxfordshire and the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. UK: Oxford International Brigades Memorial Committee, 2015.

James, Luke. “Nimby’s block nod to heroes of Spain Civil War in Oxford.” November 6, 2015. https://morningstaronline.co.uk/a-69a5-nimbys-block-nod-to-heroes-of-spain-civil-war-in-oxford-1 (accessed April 13, 2022).

Meddick, Simon. Liz Payne, Phil Katz. Red Lives: Communists and the Struggle for Socialism. UK: Manifesto Press Cooperative Limited, 2020.