What stopped Oxford booming during the Industrial Revolution and beyond?

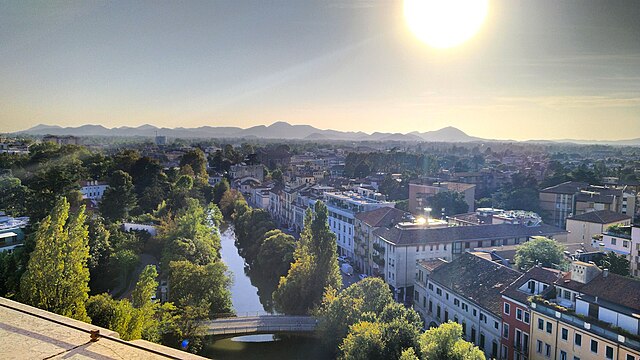

The industrialisation of Oxford, as opposed to its potential, proved somewhat anticlimactic. Located about 60-70 miles from major ports in Bristol, Southampton and London and situated along the River Thames, the city holds a strategic place in British geography. Indeed, during the 1600s, various buildings hosted four separate parliaments, the second of which took place during the Civil War at the site of Charles I’s court. Just as London Bridge sits at the point of the lowest flow on the Thames, Oxford’s Magdalen Bridge rests over the lowest point of water flow of one of its tributary streams, the Cherwell, allowing safe and easy travel at the city’s centre. Additionally, its placement away from the capital permits Oxford, unlike several other cities on the Thames, to command the region around it. Of course, it did lack the raw materials, beneficial to the growth of industrial cities, but even so from an economic standpoint, it stands that Oxford’s position on the map during the golden age of manufacturing was unsatisfactorily utilised. What then, was the cause for British industrialists to forgo the idea of a truly industrial Oxford?

Oxford began to see glimpses of industry in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as the city became more accessible to trade. In 1790, the Oxford canal was completed, which for about 15 years, acted as the principal conduit of trade between the capital and the midlands. Then in 1843 and 1851, Oxford was linked to the Great Western, and London Birmingham Railways greatly influencing both the number of passersby, and settled citizens. Brewing became quite prevalent in 1870s Oxford while water, textile and paper mills popped up around the city’s outskirts. The largest companies included W. Lucy’s Eagle Ironworks and Frank Cooper’s marmalade, although even these did not employ more than a few hundred workers.

Comparatively, urbanisation gripped Oxford in the early twentieth century. As Oxford City Council data reports, while population growth in the city from 1801 to 1911 stayed steady at about 5,000 new residents a decade, those numbers bounced to count a population increase of around 10,000 every decade until 1971. These statistics are not hard to explain; it was in 1912 that Oxford became a focus for motor manufacturing, as the highly successful Morris Motors plant opened in Cowley. The Pressed Steel Company, producers of car body parts and in 1933 refrigerators, added additional employment opportunities to the job market. Besides these, Oxford’s economy was made up of small to medium businesses of no more than 200 people. In fact, during this entire period of elevated growth, the city’s third largest business employer remained the Oxford University Press. E.W. Gilbert, a social geographer and Professor at the University of Oxford, asserts in his 1947 article The Industrialization of Oxford that “Industry at Oxford is badly balanced. As 30-40 percent of the insured population are employed in one industry, a slump in that industry would be a disaster to Oxford.” Gilbert’s claim would soon be proven correct. As car production slowed across Britain in the 1970s for a variety of reasons (such as rising contention between unions and management, outdated production models and global events such as the oil crisis in the Middle East), Oxford’s population was directly affected, slowing to an average 3,000 additional citizens a decade from 1971 to 2001.

Oxford’s layout was another huge factor that limited its growth. Due to a lack of long-term plans for the city’s housing, construction in the early twentieth century was carried out very inefficiently. It was precisely for this reason that Baron Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town and Country Planning announced on the floor of the House of Commons in 1946 that Oxford had become “grossly overcrowded” and “quite unworkable”. Later that year, Silkin met with the City Council, which agreed that “all possible steps be taken in an endeavour to prevent the population for which Oxford is the natural centre from increasing.”

Silkin’s comments on the trip, that it “was made in an endeavour to safeguard one of the country’s most precious heritages” reveal one more, less statistical aspect for the slow growth of the medieval city. It is an unfortunate truth of city building that efficient commerce blends poorly with architectural beauty, and, it seems, in the minds of many in Britain and across the world, the destruction that would accompany further urban sprawl would do nothing else but tarnish an educational landmark.

Written by MOX volunteer Eli Rasmussen.

Want to write your own Oxford-inspired post? Sign up as a volunteer blogger.